beginning

practice

know your characters

structure

dialogue & visuals

plants & pay-offs

re-writing & reading

Sitcom Writing Advice

So, you’ve had an idea for a Situation Comedy? You need to ask yourself a few basic questions. Is it viable? What are its themes? Who are its characters? Where is it set?

The easiest one to answer is this last one – it is probably the first thing you know. Perhaps you’ve identified a niche, something, somewhere, that no-one else has thought of. Beware, original settings do not necessarily make for brilliant comedy. Some of the best (and most successful) sitcoms do not have original settings – Men Behaving Badly, Only Fools and Horses or Father Ted. What sets them apart is their characters.

But also, and perhaps more importantly, they have clearly defined themes. Men Behaving Badly is just that, laddish blokes and how they affect their own environment. Fools and Horses clearly states its themes: This time next year, we’ll be millionaires. Father Ted is about the foolishness of organised religion.

Again though, these themes are for nothing without engaging characters.

And engaging does not have to mean likeable. In fact, likeable sitcom characters are boring. Gary and Tony, Basil Fawlty, Richie and Eddie, Captain Mainwaring, Del Boy, Alan B’Stard and so on, are all engaging but not entirely likeable.

Judging whether your sitcom is viable may not seem like your job. You might think that that decision lies with a Producer or a Commissioning Editor, but if you don’t know if it is sustainable, then they certainly won’t want to know. Can you outline at least six plots (thumbnail ideas will do)? Or even twelve? Can you design sub-plots around each character, or pairings of characters? But the best way to know if it is viable is to write a series of episodes (for more reasons than one). If you can’t be bothered with this, then you might just as well give up now. To be a writer, you DO need to write (duh!).

Practice

If you are unsure how to write a sitcom or how it should be structured, try writing someone else’s work. Long running, clearly defined series are the best. Try an episode of The Simpsons, or Seinfeld (these will make excellent calling cards if you are trying to get on to a long running show, but do not write an episode of the show you want to write for). American sitcoms are structured differently to British ones, so this is a beneficial exercise for many reasons.

Plot the episode, perhaps using cards, dividing it clearly into plot points, or act divisions if necessary. The act divisions on US shows work in a different way to ours – the end of Act One should present a character with a situation it seems impossible to resolve, and Act Two is generally a set piece of resolution.

The act divisions in commercial UK sitcoms seem to be there for the most part to accommodate commercials. It is not a bad idea to follow the US model, even for a commercial UK sitcom.

Characters that are not part of the main plot, should either be disregarded, or given sub-plots. Sub-plots can serve the main plot, or offer support to it, by showing a different point of view, or just providing extra jokes.

Keep asking yourself questions like: Can I see this as an episode of this show? Or Would Elaine really say that? This way you will get to know these characters, and this will help you get to know your own characters later. When the script is at a stage you are happy with, do not discard it – it will serve as an excellent sample of your writing abilities, and demonstrate that you know how to write for established shows.

Know Your Characters

This all depends on your working method. If you are anally retentive, then you will want to write complicated character bibles, charting each person’s life, which school they went to, who they have or haven’t loved, or even their curriculum vitae. If you are anally expulsive, you will want to pour things onto your blank page and discover your characters this way.

Each way is equally valid, but a word to the anal expulsive – a little planning will go a long way. Even if you just write a short paragraph for each main character, this will help focus you. I find, without focus, characters lack focus. Even if the person on the written page is different from the one in the brief outline, you’ll find the exercise valuable.

Characters should really dictate plot, not vice versa. Pro-active characters are like characters you hate, much more interesting than the passive guy who follows the flow. However, that is not to say plot should not influence character at all. It’s a fine line.

I find that the best way to get to know your characters is to put them in different situations and see how they react. The easiest way to achieve this is to write three of four draft episodes and watch them develop. Then go back and look at Episode One and see how you can implement what you have learnt.

Remember, plot arc in character development is just as important as in plot – so don’t make them exactly the same, allow them development. I would be very surprised if you do not learn anything by doing this. Also, it tests the project’s viability. With four episodes in draft form, you have an awful lot of material to work with – even if you end up distilling all four into the first episode.

You will also find that you prefer writing for particular characters in favour of others. I’m sure Father Dougal was much more fun to write than Mrs Doyle. In fact, I seem to remember Lineham and Matthews mentioning she became harder and harder to develop as the series progressed.

If you find that important characters are pushed into the periphery by the flamboyance of your favourite, try pairing them, and see what develops. You might discover something completely new about both of them. Even if this is just a test scene, it cannot do any harm.

Peripheral characters are very important, so do not under-estimate them. Kochanski in Red Dwarf became a catalyst that developed Kryten. Guests in the hotel make Basil much more funny. Watch an episode of Father Ted, and examine the peripheral characters in that. Bishop Brennan (stern, scary, imposing), Father Stone (the most boring man in the world) or even the Dancing Vicar. Each one has an over-emphasised trait, and this is an excellent tool with which to work.

Indeed, your main characters should follow this model too:- take one trait and exaggerate it. Basil is consummately rude, Lister is a slob, Alan B’Stard is a bastard, Captain Mainwairing is a pompous fool. Indeed, it is always worth studying Dad’s Army. A true ensemble piece, with clearly defined characters throughout.

Make your characters engaging, even if they are not likeable. Also, remember that not likeable does not mean irritating – we must at least be able to empathise with them, if not truly understand them.

It’s also worth looking at John Sullivan’s work, and not just Only Fools and Horses. Dear John has just been released on video, and also try and watch Citizen Smith.

Structure

If you are unsure how a sitcom should be structured, the best thing I can advise is to sit down and watch several episodes of The Young Ones, with a view to deconstructing it. This is a Media Studies tool which means you examine how, and why, certain methods are being adopted. The Young Ones is a deliberate exercise in breaking sitcom conventions. At the time (and still) it broke a lot of the traditional models, and in doing so, invented some new ones.

When you know what’s being broken, then you have learnt the traditional model. Look out particularly for the role reversals, the non-linear narrative, the irrelevant sketches, the lack of closure.

Don’t just break conventions for the sake of it. Your format and structure should be true to itself.

Last Of The Summer Wine (or any Roy Clarke comedy) has a very defined format, and even if you hate the shows, you should look at them and deconstruct them.

If you are writing specifically for a commercial channel, I do suggest you try and adopt the US model (it is not imperative), but I think there seems to be a swing towards it at the moment (at least on the ITV networks, and this isn’t necessarily wise either).

Dialogue & Visuals

Good dialogue is extremely important. Voice is even more important.

By this, I mean each character should have a distinct voice, should speak slightly differently to every other character. I don’t necessarily mean accents, or different level of intelligence, more they should have a different rhythm, a different means of delivery.

Listen to the characters on Father Ted. Ted himself is quite lucid, Dougal won’t use long words, Jack barks monosyllabically, and Mrs Doyle is fond of repetition.

Dialogue should be as realistic as possible, or at least as realistic to its own situation. The surreal fantasy world of Bottom demands a different kind of dialogue and voice to Is It Legal?. If you want to use ‘bad’ language, do so, so long as it is relevant. The restrictions on swear words are crumbling by the day (good thing) as we become less sensitive to everyday language on TV. However, there are ways around it, if it becomes a problem. Invent unique words and phrases that serve your purpose. Look at smeg. Before Red Dwarf who had heard it? I’m particularly fond of Pump as an exclamation, or Vas Deferens as a truly derogatory term (look it up in a medical dictionary).

Keep it simple. If you can use two words to say it instead of seven, then do so. Succinct is sacrosanct. Unless of course, you have a long winded character. Keep it relevant to the moment. Again, this does not mean you should not have lucid characters, but don’t bore us with over-written poetry.

One liners are great, but don’t live for them. The comedy should come first from the characters, then from the situation. If you can write one-liners that seem natural, that’s the best thing. Don’t write around a great line. A great line should be hilarious, but only in context. If the joke is good on its own – fine, but if it is better because of what sandwiches it, then that’s best.

Do not overlook the importance of visuals. That doesn’t just mean slapstick violence, but more subtle visual jokes can be funnier than your best-constructed line. Remember, TV is a visual medium, and so use it to your advantage. If you can say it with pictures, do so. If your character is a slob don’t inform us of this through the mouths of your other characters, demonstrate it to us. Have him eat his own armpit gunk. Demonstrate, don’t explain.

Nuances – perhaps this should really be in the characters section. However, nuances, I think, are very important, and will make your

characters seem more real. You could let an actor discover the nuance, but it may help them if you write it, even if they subsequently reject it. Try not to let your people just sit there and talk. Make them be doing something. Even if they are eating, try and make it unique to that character. Have her eat chocolate spread from the jar with her finger, or make him contort in his chair for no reason. Perhaps she has an irritating habit of sniffing a lot. Even if you only mention it in your first character description, it will be taken on board by actors.

The same goes for description of visual style – directors will take note, even if it is to disregard it as a possibility. More and more sitcoms are moving out of the studio, and so directors may have a free hand with which to play (oo er).

Plants & Payoffs

These are as important in comedy as anywhere else. Flatter your audience by making them remember things. Dramas with a good twist will always have had the plant, and the pay-off comes when you realise what’s going on.

This is a good tip if you want a strongly plotted episode, but it works equally effectively as a joke. For excellent examples of this look at Fawlty Towers, in particular, an episode like The Hotel Inspectors.

Plants and pay-offs are paramount to any farce. See also Joking Apart or Some Mother’s Do ‘Ave ‘Em. They can be much more subtle as well. Be creative.

Re-Writing & Reading

No matter how much you hate it, or how lazy you are, re-writing is of utmost importance. Identify weakness in plot, badly written characters, unintentional lulls in the action, jokes that could be improved or just plain boring spelling mistakes. Make the script a joy to read, and you have won half the battle.

If you feel a joke can be done better, play around with it. If you find a character is doing nothing in the scene, find something for them to do – or delete them if they are totally irrelevant. Read your own work. If you find you are bored with it, try and pep up the reading experience. But always know when to stop. Too much could kill the flow, or detract from the experience.

Try reading other people’s scripts – preferably ones that have been produced. This doesn’t mean transcripts that someone has kindly typed up and uploaded onto the Internet for you. If possible, get hold of shooting scripts (visit Drew’s Script-O-Rama), see what’s been removed and re-arranged. Ideally you should try and see the drafts that lead to the final shooting script, and try and identify weaknesses before moving on to the next draft.

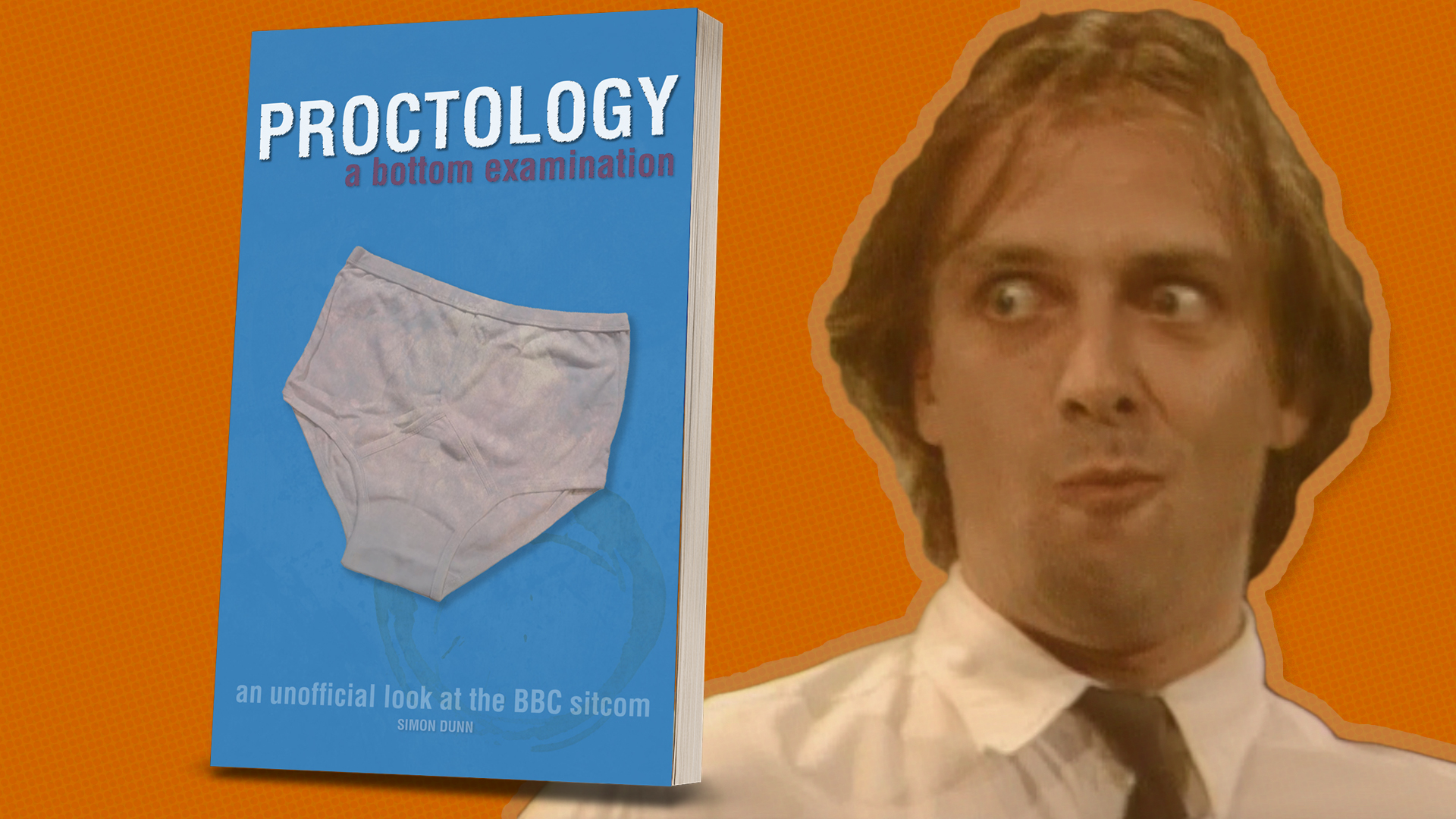

The Bottom scripts are available, as are a selection of Red Dwarf ones. Reeves & Mortimer sketch books are around (at least for The Smell Of … ), and I know A Bit of Fry And Laurie were published too. Even if these are sketch shows, you can still see work in progress. If you have to search for the material, then do so, it can only benefit your writing.

You can subscribe to my mailing list here. I won’t share your email address, and you’ll only get one message every few months.

Finally, I cannot recommend it highly enough, but The Tools Of Screenwriting is a book you should own.